For decades, airline loyalty programs were designed to reward one thing above all else: flying … and flying a lot.

Fly more, earn more miles. Fly even more, earn elite status. Redeem those miles at the same rates as everyone else. That’s more or less how it’s worked since the inception of frequent flyer programs.

But that social contract is breaking down.

Today, if you want access to the best versions of many airline loyalty programs – the lowest award prices, better award availability, and predictable value – flying is no longer enough.

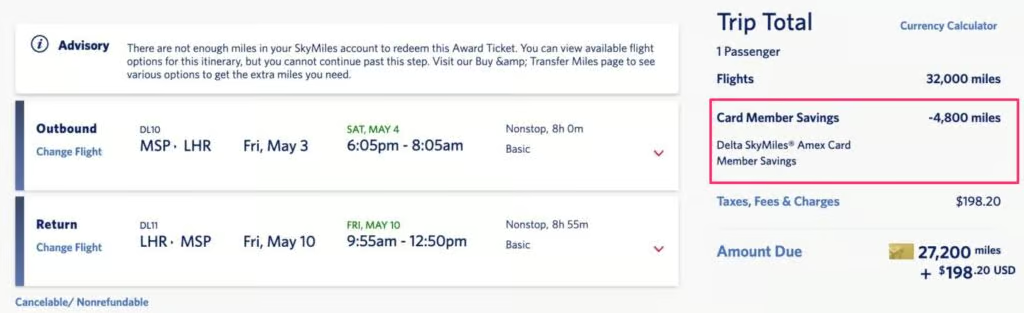

Delta was one of the first major U.S. airlines to make this shift explicit. In early 2023, it launched TakeOff 15, followed up by broader changes to its SkyMiles American Express portfolio the next year. This benefit gives eligible cardholders at least 15% off the mileage cost of any Delta-operated award flight. On paper, it sounded like a generous new perk. Delta framed it as a win – and to be fair, for cardholders, it is. But it also reset expectations in a way that’s hard to unsee once you notice it.

From that point on, there were effectively two prices for every Delta award: the one Delta expects engaged members to pay, and a higher price for everyone else. Because SkyMiles pricing is fully dynamic and Delta no longer publishes award charts, this reset didn’t require an announcement or trigger much backlash. It simply changed the baseline. Over time, it’s become clear that Delta now assumes anyone serious about redeeming SkyMiles holds a Delta Amex. If you don’t, you can still use your miles, but you have to pay more.

That change matters even more once you look at how tightly Delta controls premium cabin awards. Long-haul Delta One seats are rarely bookable through partner programs like Virgin Atlantic or Air France/KLM Flying Blue at all. In practice, premium cabin Delta awards have essentially become a SkyMiles-only proposition. TakeOff 15 simply ensures that the best version of SkyMiles pricing is reserved for its cardholders.

United has taken the same idea and pushed it further … and more visibly.

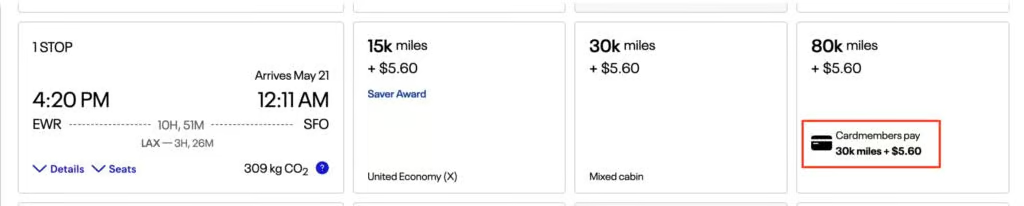

Earlier this year, United began displaying “Cardmembers pay” pricing directly on MileagePlus award searches. Non-cardholders now routinely see two prices for the same flight: the regular mileage cost and a lower price available only if you hold a United credit card. Sometimes the difference is modest. Other times, it’s dramatic – tens of thousands of miles less for the exact same seat.

What’s important is that United isn’t just offering a blanket discount. In many cases, it appears to be offering entirely different award inventory to cardholders – closer to traditional saver-level space that has otherwise become increasingly scarce. And unlike Delta, United is showing non-cardholders exactly what they’re missing, turning the booking page itself into a live credit-card pitch.

That didn’t come out of nowhere. United has long offered expanded saver-level award availability to MileagePlus cardholders on United-operated flights. What’s changed is how explicit and how layered the strategy has become. Not only do you get a cheaper rate by holding a United card, but the airline appears to hold back some saver-level Polaris award space that’s only visible when logged into a MileagePlus account tied to a United credit card.

The impact extends well beyond business class, though. Extra saver availability on United’s domestic flights – even in economy – can materially change what trips are possible to book. Cardholders are more likely to find saver-level space from smaller home airports to major hubs, which makes it far easier to connect onto long-haul partner flights.

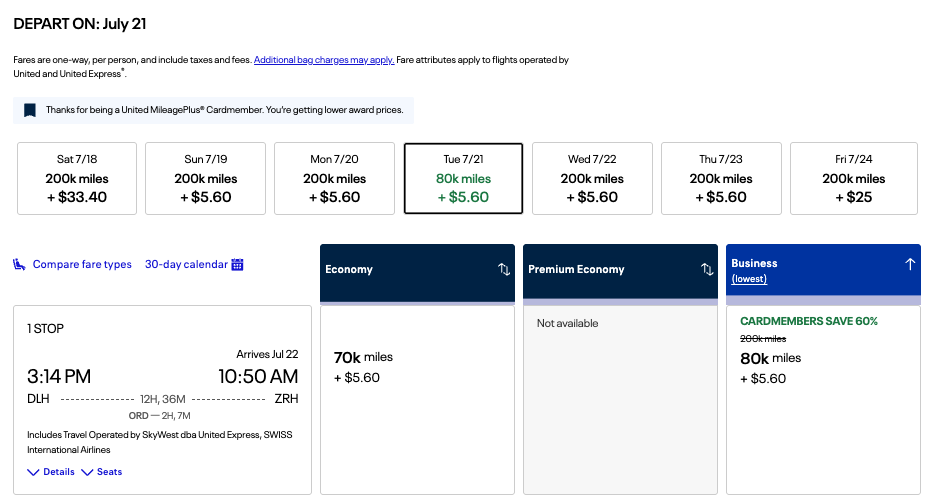

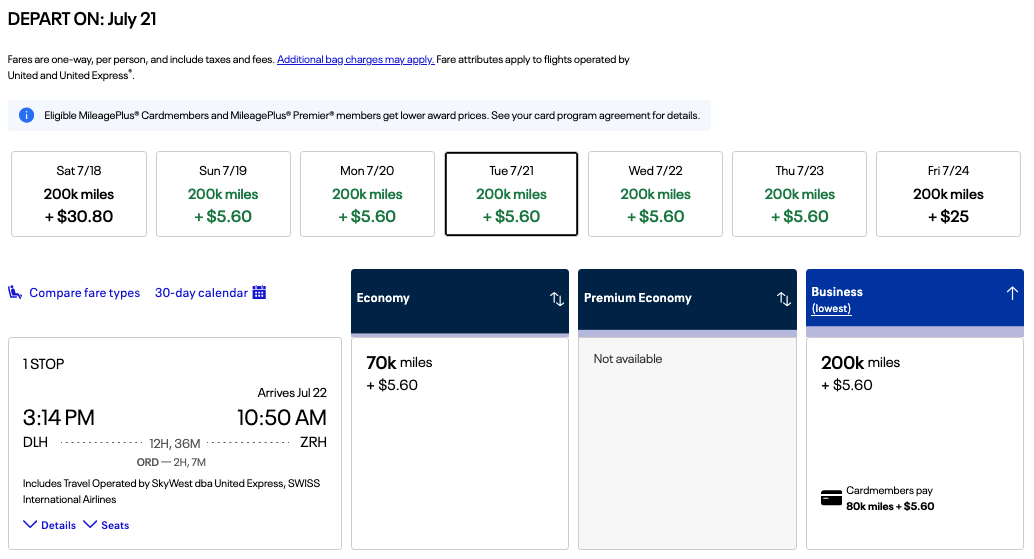

In practice, a United cardholder might be able to book a single saver-level award from a regional airport like Duluth (DLH), Minnesota, through Chicago-O'Hare (ORD) to Zurich (SRH) on SWISS.

A non-cardholder, seeing no saver space on the domestic leg, may be forced to book a separate positioning flight or start their award in Chicago instead … or give up entirely.

United made its intentions even clearer earlier this year. In October, the airline cut award prices on partner airlines like Lufthansa, SWISS, ANA, and Asiana by nearly 10%. A transatlantic business-class award that had long cost 88,000 miles each way was suddenly pricing out at 80,000 miles for everyone. It looked like a rare consumer win. By November, those lower prices were gone for non-cardholders, but quietly preserved behind the “Cardmembers pay” banner.

At that point, it was hard to argue this was just clever marketing. This was structural.

This Isn’t Just About Credit Cards

Delta and United are the most aggressive U.S. examples, but they aren’t alone in rethinking who gets access to the best award pricing and inventory.

Air France-KLM’s Flying Blue program now gives top-tier elites priority access to its lowest award prices – sometimes cutting the mileage cost by more than half. And beyond elite status, Flying Blue has gone a step further by introducing Flying Blue Extra, a paid subscription that gives members access to improved award availability and discounted award pricing.

Importantly, Flying Blue Extra isn’t limited to European residents or elite flyers. Anyone can sign up, regardless of where they live – effectively allowing members to pay for access to a better version of the loyalty program.

Emirates offers another stark example of how airlines are gating access to their most aspirational awards. Earlier this year, the Dubai-based carrier changed its Skywards program so that Emirates First Class awards can only be booked by members with elite status. Even if you have the miles, you can’t book a first class seat unless you’ve already cleared the airline’s loyalty bar.

It’s a clear signal that simply earning points is no longer enough. Access to the best redemptions increasingly depends on who you are to the airline, not just how many miles you have.

Colombia-based Avianca takes a similar approach with LifeMiles+, which sells discounted award pricing outright through a subscription. And airlines like Cathay Pacific and Qatar Airways increasingly reserve premium cabin award space for bookings using their own miles, sharply limiting partner access.

While the levers are different, the outcome is the same.

The common thread isn’t just credit cards themselves – it’s segmentation. Airlines are no longer pretending all members should see the same prices or award availability. They’re determining who their most valuable customers are and designing loyalty programs tailored to them. In the U.S., credit cards are the most powerful lever, generating billions in predictable, recession-resistant revenue without requiring customers to actually fly.

And as transferable credit card points have made it easier than ever to earn miles without committing to a single airline, this is how airlines are pushing back – by reserving their best pricing and inventory for travelers fully inside their ecosystem.

Delta has said it expects to earn up to $10 billion from American Express in the long run. United wants to double loyalty revenue by the end of the decade. Against that backdrop, it’s no surprise loyalty programs are increasingly being optimized for frequent spenders, not frequent flyers.

Bottom Line

Airline loyalty programs are no longer built primarily to reward flying. They’re built to reward buy-in.

Delta reset expectations in early 2023 by baking cardholder-only discounts directly into its SkyMiles program. United has gone further by stacking better pricing, better availability, and real-world booking advantages behind its credit cards … and showing everyone else what they’re missing. And globally, airlines are becoming far more comfortable gating their best awards behind paywalls, status tiers, or proprietary ecosystems.

If you plan to earn and redeem miles primarily with one airline, holding its co-branded credit card is no longer a “nice-to-have.” It’s how you avoid paying a loyalty tax.